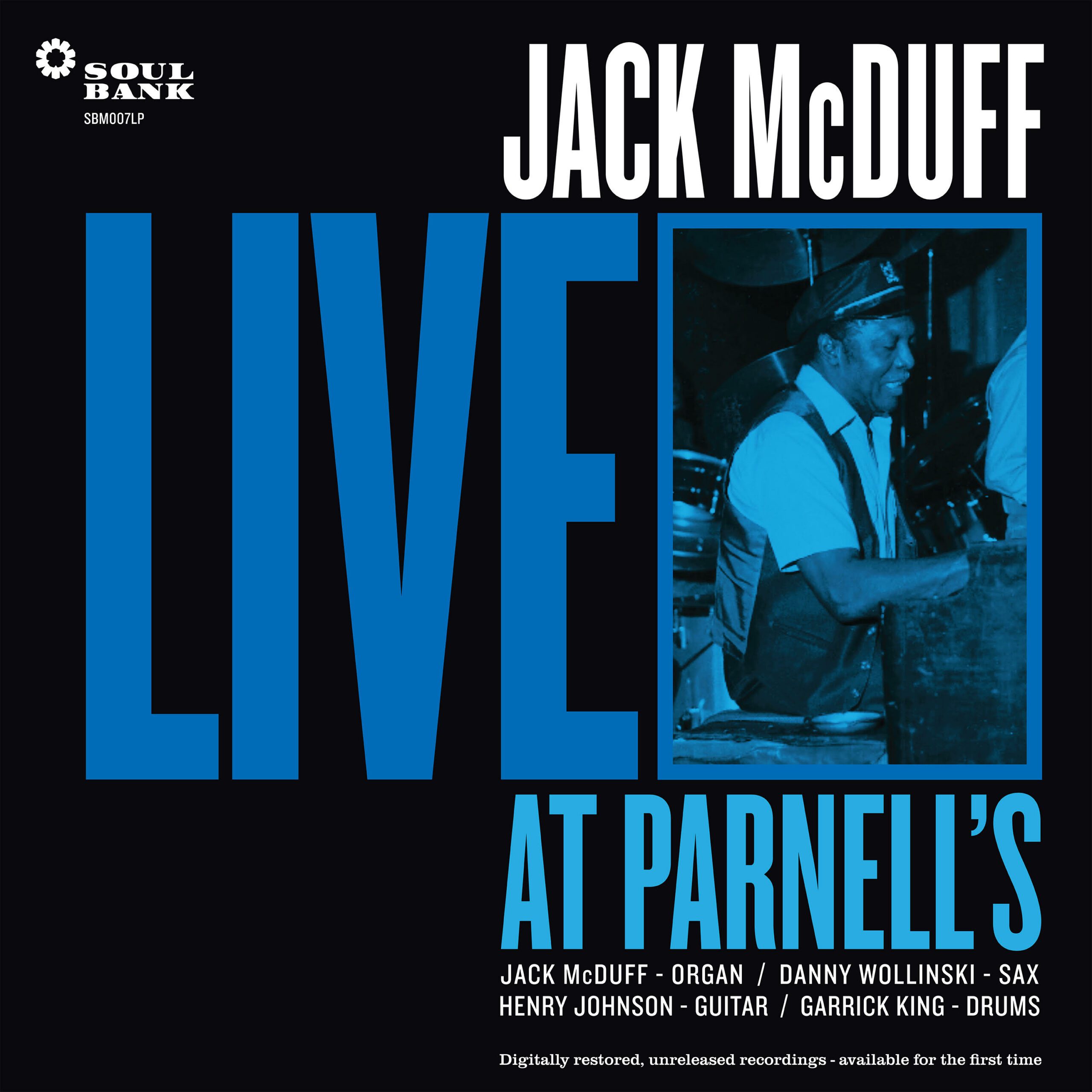

In June 1982, influential US jazz organist, ‘Brother’ Jack McDuff (1926-2001) and his group, Danny Wollinski on sax, guitarist Henry Johnson and drummer Garrick King, played a week-long residency at Parnell’s, a club in Seattle.

Forty years later, these rare and hitherto seemingly lost recordings of the concerts have finally seen the light of day. The recordings were made by jazz organ aficionado and friend of McDuff’s, Scott Hawthorn, on a C60 cassette from the venue’s fairly basic sound desk. They’ve been released as the 15-track Live at Parnell’s, on the Soulbank Music label, as a three-LP set, or double CD.

Soulbank boss, Greg Boraman, first heard the live recordings back in 1999, when Hawthorn made them available to listen to online as MP3 files, but there were serious issues with the audio quality.

The cassette had degraded over the decades, and, during the concerts, McDuff’s Leslie speaker cabinet – he played a Hammond B-3 organ – had a rip in the bass woofer, which, when he stepped on some of the pedals, created a very loud buzz, which was clearly audible.

In order to release acceptable commercial versions of the recordings, Boraman sent them to Claudio Passavanti, from UK-based mastering and audio production company Doctor Mix.

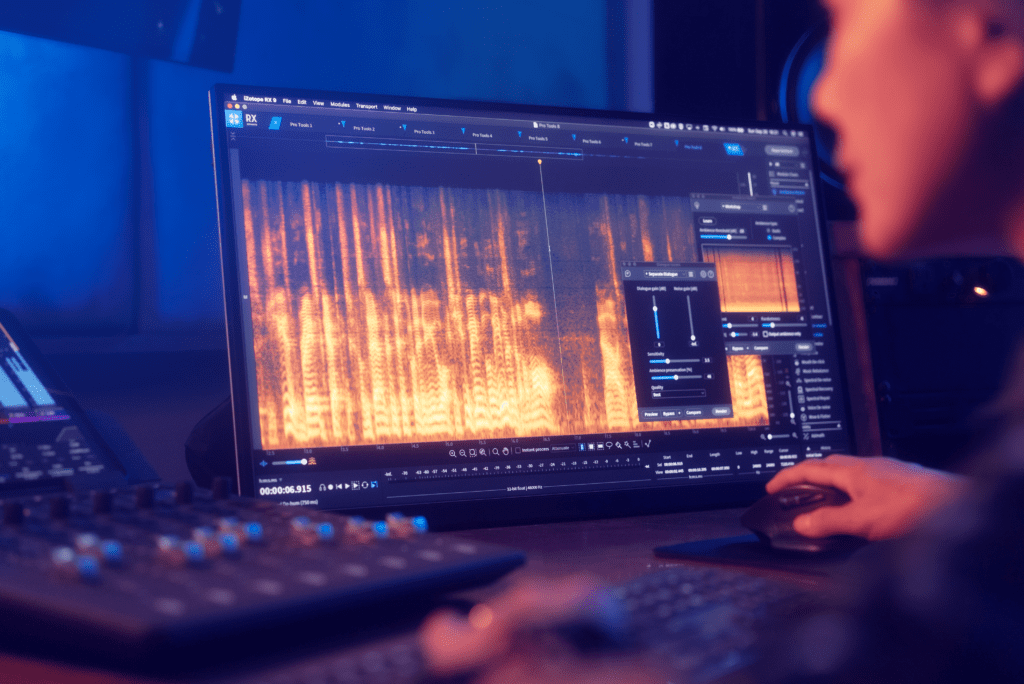

He assessed them and then started the process of restoring and transforming the material using AI-based audio software called RX9, which was developed by specialist company iZotope.

Passavanti was helped by Christoph Härtwig and his development team at iZotope, who acted as consultants on the project.

For the vinyl version of Live at Parnell’s, Boraman approached London cutting house, The Carvery, which further tweaked Passavanti’s work so it could be used to cut the lacquers specifically for the vinyl format.

hi-fi+ spoke to Passavanti and Härtwig to discover the challenges they encountered when restoring the recordings, how they overcame the difficulties with the use of cutting-edge AI audio technology and what they achieved with the results.

Claudio Passavanti : founder of Doctor Mix

SH: What did you first think when you got involved with the McDuff project? Did you see it as being a major challenge?

CP: When it came to us, the recording wasn’t a high-resolution one – it was on a [cassette] tape. One of the challenges was that the signal to noise ratio was barely acceptable and because it wasn’t a professional medium, the tape wobbled a lot.

The recording needed fixing. There were all kinds of problems – the stereo field was crooked.

The first thing we did was to stabilise the sound. There were variations in pitch – wow and flutter – so technology like AI really made a difference.

The neural network somehow recognised the variations in the transportation of tape rather than in music.

Then we had all the background noises – sometimes the magnetic field can affect the tape and mask the top frequency. We had to make up for what was lacking.

What about the faulty organ sound? How did you deal with that?

Besides the recording problems and the lack of depth and the weakness of the signal, there was a problem with the organ itself – don’t forget, this was a gig that wasn’t meant to be recorded.

The organ had a broken speaker – on certain notes, it would vibrate and make a nasty noise.

What you hear now on the recording is 10 times better because we were able to address it and reduce it – we went to every part and manually fixed it using spectrograms and AI to identify the foreign distortion.

There is a limit, of course – if the sound isn’t there, you can’t invent it, but if there is an extra sound on or distortion on top of it, you can remove it, because the distortion is louder than the sound itself.

Thanks to today’s technology, the limit is light years ahead of where we were 10 years ago – it’s ground-breaking.

You can remove vocals from a record, which was considered black magic up until a few years ago. It would’ve been unthinkable to take a tape recording and get a decent sound out of it that you could press on vinyl. It’s life-changing in music.

How long did you work on the project?

It took weeks because firstly I had to go through all the material and understand what the problems were – then I had to use different tools within the software to address them.

Are you pleased with the results?

I am shocked because when I first got the recordings, I thought it was impossible to release them.

With iZotope’s help we could push the envelope – we took it to the very limit.

It’s a compromise – I know how records of the same era sound, so I didn’t want to make the mistake of making it sound ‘hi-fi’. That’s not a sound that’s real or authentic to that time.

Knowing the style, the references and the culture behind it is the hard part – you need a producer, a musician and a record collector or connoisseur. in order to get that right.

Christoph Härtwig product marketing manager, iZotope

SH: Can you tell us about iZotope’s RX audio software technology? How did it come about?

CH: It was invented by a guy called Alexey Lukin, who is our principal software engineer. He started using AI to remove common problems in post-production on audio material and he invented RX to get rid of unwanted noises – it’s become famous for its de-noising algorithms, which are pretty much industry standard.

It was created to solve noise problems while producing audio for films but now there are use cases where it’s taking care of audio for archive material that is being digitised.

Over time, RX has also become a tool that music producers use because even in the studio there’s hiss, like when you use old compressors, but it’s not taking the soul out of the music.

On the McDuff project, I guess you could’ve stripped out most of the unwanted noise, but, as you say, you didn’t want to lose the soul or the live feel of the recordings…

Exactly. Some modern producers use RX as a creative tool, but it’s made for restoration.

If you have to repair audio, the first thing that comes to mind is RX.

How did you hook up with Claudio Passavanti of Doctor Mix?

I’ve known him for a long time – he called me and said he had a recording with a broken Leslie cabinet that he had to deal with. He asked me what we could do. We took a closer look at it – the actual repair process didn’t take too long because RX is really clever.

We did some ‘spectral repair’ – the software looks at the music like it’s a picture. You can see the noise on a spectrograph and take it out. The repair took maybe a couple of hours – the first pass to see if it works is about five minutes, but the part that takes longer is when you have to render it in high quality.

When you’re working with compression or audio data, it can result in lossy audio or artifacts – that’s when you have to tweak it.

Have you heard the finished album?

I’ve only heard snippets and it sounds really good. I hope I can get a vinyl version – I’m looking forward to that.

I’m a vinyl head – I love it because of the noise – but there are definitely advantages with digital.

What’s next for AI in audio? Where’s it heading?

That’s a good question. The quality is improving – I’m a sound engineer and we can do things today that wouldn’t have been possible 20 years ago.

If you have a stereo file, you can increase the volume of the drums alone – you don’t have to have the stems. That came about a couple of years ago and it was a ‘wow’ moment in the industry. When it comes to RX, the algorithms will improve so that you will be able to remove noise or repair more complex audio.

On the music side of things, I think AI will lead to auto-generated music. It exists already, but it’s not very good.

I’m a guitar player – nobody will ever be able to copy a real instrumentalist, or his or her flaws, but AI will help people who thought they’d never be able to make music to do so.

I think that’s where it’s heading – it will enable us to create better audio and the quality will improve.

Live at Parnell’s by Jack McDuff is out on Soulbank Music. It’s available on vinyl (three-LP) and double CD.

By Editor

More articles from this authorRead Next From Music

See all

Depeche Mode: Memento Mori

- Apr 22, 2024

Music Interview: Jah Wobble

- Mar 27, 2024

Music Interview: Don Reedman

- Mar 27, 2024

Album Review: Orbital – Optical Delusion

- Mar 20, 2024