Watch the road, please!” shouts Jesse Malin.

He’s speaking to the driver of the van he’s sat in while talking to hi‑fi+ on his phone from somewhere in the middle of Pennsylvania – he’s just played live on a morning radio show.

“It looks like we’re going to drive into a wall while we’re doing this interview,” he tells us.

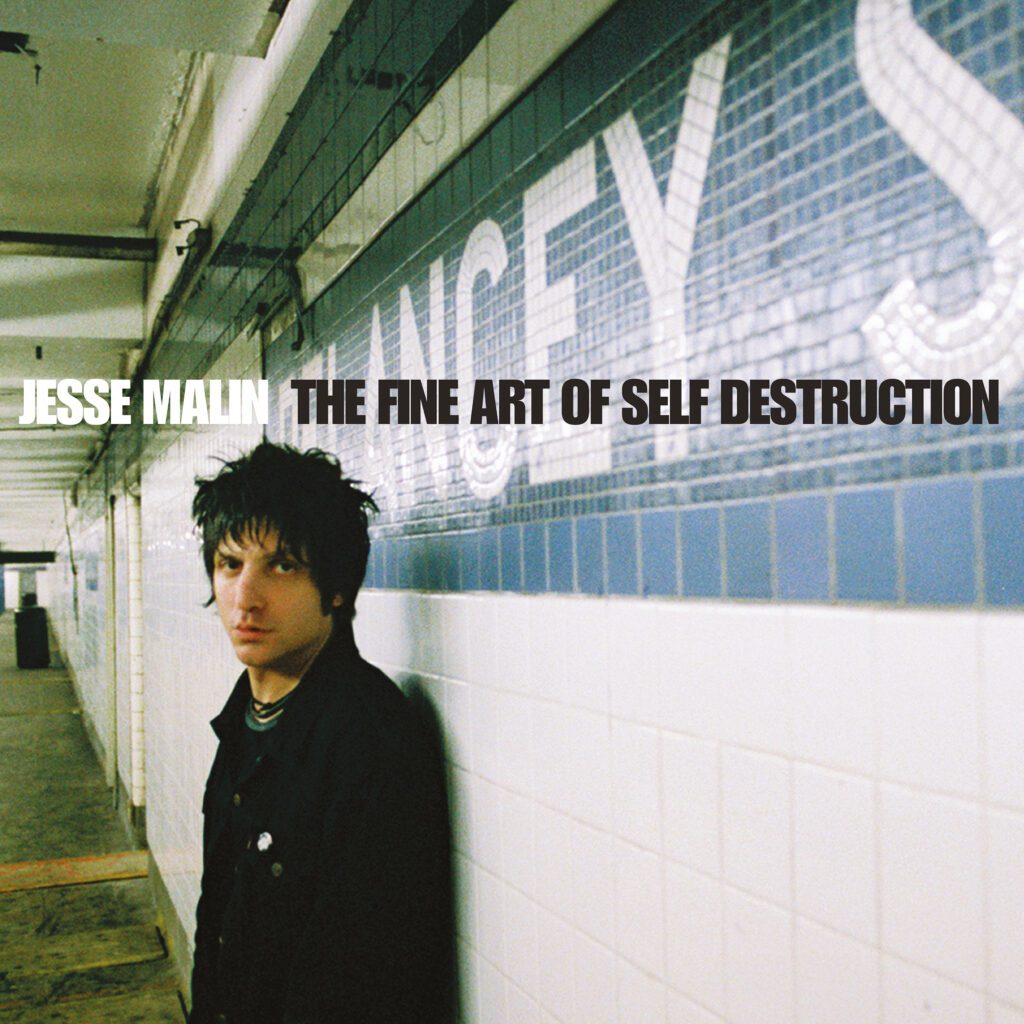

That would be ironic considering the record we’re here to talk about is the New York singer-songwriter’s debut album, The Fine Art of Self Destruction, which recently celebrated its 20th anniversary – it was released in early 2003.

To commemorate its special birthday, the record is being reissued as a two-LP set, one of which is a reimagined and rerecorded version of the album. There’s also a UK and European tour in February/March.

Produced by Ryan Adams, The Fine Art of Self Destruction was recorded live and raw over six days in New York.

It’s a wonderful and poetic debut record that perfectly captures the feel of the city it was made in – an atmospheric and wintry set of rough and ready rock ‘n’ roll tunes, alt-country troubadour tales and festive-themed ballads about failed relationships, populated by characters Malin met on the streets of New York.

Prior to going solo, he had been in hardcore band Heart Attack as a teenager, and during his twenties he fronted glam-punks D Generation.

He then left to pursue a solo career – hi-fi+ asks him to cast his mind back to when he first started writing the songs that would end up on The Fine Art of Self Destruction.

“I was still learning how to sing and tell stories,” he says. “Those songs were written in a little apartment downtown, without a record deal, a manager, or any expectation of anything coming of it – just a need to write them.”

SH:The Fine Art of Self Destruction just turned 20 years old. How does that feel?

JM: It’s surreal – it’s very odd. I’m proud of it – I still play a lot of those songs in the set and it’s the record that kind of got me started as a solo artist after being in groups. It started the next chapter of my life, but it’s a lesson in how fast life can go by. So much has changed, but certain things are still similar.

You were in your mid-thirties when you made it…

Yeah – I’m 55 now. Twenty years ago, I went to the UK and Europe on tour – it was a whole new life. I did some great tours with Ryan Adams and Counting Crows, and then on my own – I really got to connect with UK audiences.

I’ve been so lucky to keep that friendship and that crowd – I’ve watched them grow up and have kids.

I feel like some of the songs have grown up – they’ve gone through changes from being on the road and getting dirtied up over the years.

I’ve learned about the songs… It’s all experience – it’s very different than just writing a record that I did as a labour of love just ‘cos I needed to.

I recorded it very quickly – I didn’t even have a record deal or any real plan, except I knew I had to make this record and that it was going to be a change for me artistically. I wrote it in a little apartment, in the coldest part of the world, in Manhattan.

Why did the time feel right to do something different?

I wanted people to hear the songs. I always felt that in my previous groups the lyrics were very important, but I wanted to make some space for them – to make things a little quieter.

I’d been organising the bands and paying for rehearsals – I was doing all that anyway, so I might as well call it ‘Jesse Malin’, because if somebody leaves the band, unless you’re very schizophrenic, you can’t really break up with yourself.

It was easier to move that way, but it was scary, because it seemed very adult to go under my own name – it seemed serious and not very punk rock or rock ‘n’ roll, but I realised that was just my own anxiety and perception of it…

I’ve always loved gangs and I love bands. I’ve always been in bands. Even to this day, I try and play with the same people for long periods of time if I can – the people who played on the records.

I like to have that kind of comradery and community, and to bring that gang feeling on stage, but there’s also a flexibility – I can go out solo, or in a duo, and play stripped-down, with an acoustic guitar, which is how the songs were written.

Having an acoustic guitar is kind of like having a whole band – it’s very percussive… When I was a kid, I started out busking in the subway – there’s an energy to that.

Why have you re-recorded the album as a bonus disc?

We’ve been playing these songs for 20 years – we’ve grown up with them, their meanings and the characters involved.

If we were going to have a bonus disc, we wanted to do something different musically and also for a laugh – to have reimagined versions. We had some fun with it – some came out great. It really runs the gamut.

What can you remember about writing the songs that would end up on The Fine Art of Self Destruction?

I wrote them all on a little shitty Yamaha acoustic guitar, on East 3rd Street in Manhattan, between 2nd and 1st Avenue.

It was known as the safest block in New York City because it was directly across the street from the Hells Angels motorcycle chapter. They watched out for the bikes – nobody had bars on their windows, and this was when Manhattan was pretty f***ed up and full of junkies and robbers and shit.

Some slumlord bought the building and gave me money to leave – I was only paying $400 dollars’ rent. So, I took the money and paid off some bills, so I could walk on some other blocks where I owed money, and I used the rest of it to pay for The Fine Art of Self Destruction, which we did in six days.

It was the first album that Ryan Adams produced, wasn’t it?

Yeah, and he played lead guitar on the record.

How did you hook up with him?

We met in North Carolina when I was in D Generation – he came to a gig. He liked the stuff we did back then – we connected. We bonded over songwriting, and he really appreciated the attitude of punk rock.

He started out with Whiskeytown and by the time he went solo he was living in New York, and we were hanging out a lot, just walking around, writing songs and talking about songs. It was a real feeling that New York had a new energy. He said he would come into the studio and do my record in-between tours – he was out with the Gold album.

We did it in six days – I think he showed up for five. We were looking for a lead guitarist, but one day he just went to a music store in Chelsea, picked up a Strat, brought it down to the loft, played one rehearsal with us and then wrote all the guitar parts.

It’s a raw-sounding record…

Yeah – when I listen to it, I can hear a lot of growing pains, but it was a record I needed to make lyrically too – I wasn’t just writing for five other people.

I could say anything personal – go into my personal life – take my whole psychology couch and throw it up on the board, with microphones.

Where did you make the album?

In a place called Loho on Clinton St – it got taken over by The Blue Man Group. We had an engineer called Tom Schick – my manager found him. He’d done some stuff with Sean Lennon, Yoko and Bob Dylan, and he ended up doing a bunch of records, like Cold Roses and Jacksonville City Nights with Ryan Adams and The Cardinals. Now he works exclusively for Jeff Tweedy and Wilco in Chicago. He’s very good.

The band I had was the core band I had from touring a bit, and then Ryan joined – the sessions just kind of went down. We did it on the floor in the room, like a rehearsal. There weren’t a lot of overdubs.

The record sounds like it could’ve only really been made in New York – it captures the feel and the mood of the city where you grew up and lived. Was that intentional?

I don’t know if it was intentional – I think it was just actual. You write about what you know – I couldn’t afford to live anywhere else, so it was just a product of the environment.

As much as notes and lyrics are characters in a record, the place where you make it sometimes seeps into the album. That’s just what it was – being true to your school… I’ve made records in L.A. or down south and it’s been a different experience.

In L.A. you give a record a car test – you listen to hip-hop mixes in a car, in a parking lot.

We give it a bar test – we take it over to somebody’s bar and say, “Can we play this?” You listen and see it how it sounds while you’re drinking.

Did you write The Fine Art of Self Destruction during the winter? Most of the record has that kind of vibe. You mention ‘Christmas’ in the lyrics of the song Brooklyn and one of the tracks is called Xmas…

I did write a lot of it in the winter, and it was recorded in the winter too, in January. It was written in the fall too – Christmas, changes… holidays can be significant. You look at timestamps of where you were and as the seasons close in on us… It makes you think. There’s definitely a Christmas feel to Xmas and Brooklyn – in fact we toured the record in the winter, and we’ll be touring it in the winter again.

Everyone assumes the title of the album is about drink and drugs, but it doesn’t really come from being f***ed up, does it?

It’s more of a spiritual thing – my parents’ marriage broke up and everyone I grew up with, their folks got divorced in the ‘70s. Maybe it was the Pill – women could go and do whatever they needed. They didn’t have to put up with the bondage of ‘50s and ‘60s marriages – people broke up things. When I was a kid, I used to like to break up my toys with my cousin and then I broke up bands…

When I looked back at my life, I had all these broken relationships, and I had to find a way to change that by acknowledging it. A lot of people thought I was a big junkie or a drinker and that the album title was about partying, but it’s quite the opposite – it’s more of an internal, emotional and spiritual destruction.

What sort of frame of mind were you in when you wrote the songs? Some of them are quite sad…

I always feel that sad songs make me happy because they make me feel like I’m not alone – there’s somebody else out there that feels the same way, and that it’s okay to be weird, depressed, sad, hyper-anxious or an outsider. Rock music has always spoken to me and said that.

A lot of the record was based on a couple of different women I’d had heartbreak from and split up from – sometimes you write songs like little Cupid’s arrows to send a message to someone if you know they’re listening.

You’re using that medium to say something to a person, but you might not be able to contact them, so you say it to the world. There’s a lot of sadness but when you have a place to exorcise those demons you can overcome them.

The Fine Art of Self Destruction 20th anniversary expanded edition is out now on two-LP and digital (One Little Independent records).

Images by Paul Storey, Vivian Wang and Giles Edwards

By Sean Hannam

More articles from this authorRead Next From Music

See all

Depeche Mode: Memento Mori

- Apr 22, 2024

Music Interview: Jah Wobble

- Mar 27, 2024

Music Interview: Don Reedman

- Mar 27, 2024

Album Review: Orbital – Optical Delusion

- Mar 20, 2024